When you step into an IKEA store, you’re not just walking into a furniture showroom—you’re stepping into a brilliantly staged psychological masterpiece. IKEA isn’t just a retailer; it’s an experience, a journey, and, for many, a test of willpower to avoid overspending. From selling $50 billion worth of products annually to serving millions of Swedish meatballs, IKEA is more than a furniture giant—it’s a cultural phenomenon. But beneath the polished veneer lies an extraordinary tale of triumph, innovation, and controversy.

This is the wild, true story of IKEA, a company born from the humble beginnings of a dyslexic farm boy, tainted by a dark history, and shaped by groundbreaking business strategies. Let’s unravel this incredible saga.

Chapter 1: A Tragic Beginning

In the late 19th century, Achim Kamprad, a German aristocrat, defied societal norms by marrying Franziska, a woman from a lower class. Shunned by his family, Achim moved to a tiny Swedish village with his wife, where he purchased a 450-acre farm to start anew. However, tragedy struck when financial struggles and rejection from local banks drove Achim to take his own life, leaving a pregnant Franziska to fend for herself and her children.

Ingvar and this sister Kerstin, 1932

Franziska, resilient and determined, transformed the farm into a thriving business. Her perseverance and hard work became a cornerstone of the Kamprad legacy. Decades later, her grandson, Ingvar Kamprad, was born in 1926. Raised on this farm, Ingvar showed entrepreneurial flair from an early age, selling matchboxes, Christmas cards, and lingonberries to make a profit. Encouraged by his grandmother, young Ingvar reinvested every cent, eventually laying the foundation for what would become IKEA.

Chapter 2: The Birth of IKEA

As a teenager, Ingvar Kamprad ran his company from home in Elmtaryd. In a small shed he kept packages that were to be picked up by the milk-collecting lorry in the morning – IKEA Museum

At just 17, Ingvar officially launched IKEA in 1943, initially selling small household goods through a mail-order system. The name IKEA combined his initials (Ingvar Kamprad), the name of his family farm (Elmtaryd), and the nearby village (Agunnaryd). With no physical store, Ingvar operated out of a shed, mailing catalogs to customers and fulfilling orders by sourcing cheap, everyday items and selling them for a profit.

The turning point came in 1948 when IKEA expanded into furniture, a move inspired by Sweden’s post-World War II housing boom. By sourcing furniture locally and giving products memorable names (to accommodate his dyslexia), Ingvar made IKEA stand out. His innovative approach to design and distribution quickly gained traction, setting the stage for the company’s meteoric rise.

Chapter 3: The Swedish Furniture Wars

The 1950s marked a turning point for IKEA, but it wasn’t without fierce resistance. As IKEA’s affordable, stylish furniture gained popularity, it began to disrupt Sweden’s traditional furniture industry. This didn’t sit well with established players, who saw IKEA’s pricing strategy as a direct threat to their dominance. Fueled by fear, the National Association of Furniture Dealers banded together to crush IKEA before it became unstoppable.

Sweden Trade Fair, 1950s

At the heart of their battle were Sweden’s trade fairs, essential events for showcasing furniture. Unlike most competitors who displayed brochures and samples, Ingvar Kamprad went a step further—he brought entire pieces of furniture and sold them on the spot, drawing crowds eager for his unbeatable prices. The association retaliated by lobbying to ban IKEA from selling at these fairs. Ingvar, ever the strategist, set up shell companies to circumvent the rules, continuing to sell furniture under different names.

The feud escalated as trade fair regulations grew stricter. First, selling was prohibited entirely; then, displaying prices was outlawed. Ingvar countered by hosting his own fairs in major Swedish cities, where customers flocked in droves. This game of cat and mouse painted IKEA as the underdog, earning public sympathy and further fueling its growth. Ingvar’s resilience frustrated competitors, who likened him to a hydra: cut off one head, and two more grew in its place.

But the furniture dealers saved their most devastating tactic for last. They issued a chilling ultimatum to suppliers: “Sell to IKEA, and you’ll lose all business with us.” This embargo sent shockwaves through IKEA’s operations. Suppliers abandoned the company en masse, forcing Ingvar into a corner. The situation seemed dire, but once again, Ingvar’s ingenuity shone through.

To survive, IKEA adapted. Ingvar rewarded the few loyal suppliers with faster payments and better terms, fostering deep loyalty. Simultaneously, IKEA began designing its own furniture, tweaking existing designs to circumvent supplier restrictions. The real breakthrough, however, came when Ingvar turned to Poland. By sourcing wood and manufacturing there, IKEA not only escaped its Swedish rivals’ grasp but also slashed production costs, laying the foundation for its global supply chain. This turning point transformed IKEA into a formidable player, armed with a unique product line and a robust, international supplier network.

The Swedish furniture wars may have been intended to destroy IKEA, but instead, they forged its resilience. Ingvar later remarked that the boycott had been a blessing in disguise, forcing the company to innovate, differentiate, and grow stronger. By the end of the 1950s, IKEA was no longer just a furniture retailer—it was a movement poised to redefine the industry.

Chapter 4: The IKEA Effect

Sometimes, innovation strikes in the most unexpected ways. For IKEA, one of its greatest breakthroughs came from a seemingly minor logistical hiccup. One day, while preparing to transport a table back to storage after a photoshoot, an employee noticed how much space it occupied in its assembled form. His offhand suggestion—“Why not take off the legs?”—sparked an idea that would revolutionize IKEA’s business model forever: flat-pack furniture.

Flat Pack Furniture

The concept of flat-packing was deceptively simple yet transformative. By disassembling furniture into smaller components, IKEA drastically reduced packaging sizes, allowing for more efficient storage and transport. This innovation cut down on shipping costs, minimized the risk of damage during transit, and made global distribution faster and more cost-effective. Customers, too, benefited, as they could now transport their purchases home immediately, bypassing delivery delays. IKEA’s flat-pack furniture didn’t just solve a logistical problem—it redefined how furniture was bought and sold.

But flat-packing didn’t just save money—it created a psychological phenomenon that researchers later dubbed the “IKEA Effect.” By requiring customers to assemble their furniture at home, IKEA unwittingly tapped into a unique cognitive bias. The act of building their own furniture gave customers a sense of accomplishment and ownership, leading them to value the products more highly than if they had arrived pre-assembled. What could have been seen as a chore became a source of pride, fostering an emotional connection between customers and their purchases. This clever twist turned assembly into a feature rather than a drawback.

By the late 1950s, flat-pack furniture had transformed IKEA from a scrappy mail-order company into a trailblazer. Its success wasn’t just about cost-saving logistics or clever marketing—it was about understanding and shaping consumer behavior. Customers no longer saw IKEA as just a store; they saw it as a brand that invited them to take part in the process, offering not just furniture but a sense of achievement and ownership. The flat-pack revolution solidified IKEA’s status as an industry leader and set the stage for its ambitious global expansion.

Chapter 5: An Empire Built on Psychology

By the 1960s, IKEA was already a rising star in Sweden, but Ingvar Kamprad had far greater ambitions. The success of the company’s first few stores convinced him that IKEA wasn’t just selling furniture—it was creating an experience. Armed with this insight, Ingvar set out to design IKEA stores that would not only maximise sales but also leave customers eager to return. This was the beginning of IKEA’s transformation into a global retail powerhouse.

At the heart of IKEA’s strategy was its unique store layout—a carefully curated customer journey that mimicked a one-way path through a maze. Ingvar recognised that the more time people spent in the store, the more likely they were to make unplanned purchases. From the moment customers entered, they were guided through a winding path that showcased the entire IKEA collection. Each curve revealed new room setups, sparking inspiration and tempting customers to buy items they hadn’t planned on. Even the store’s vast size and single entrance-exit design were deliberate, subtly encouraging customers to linger longer.

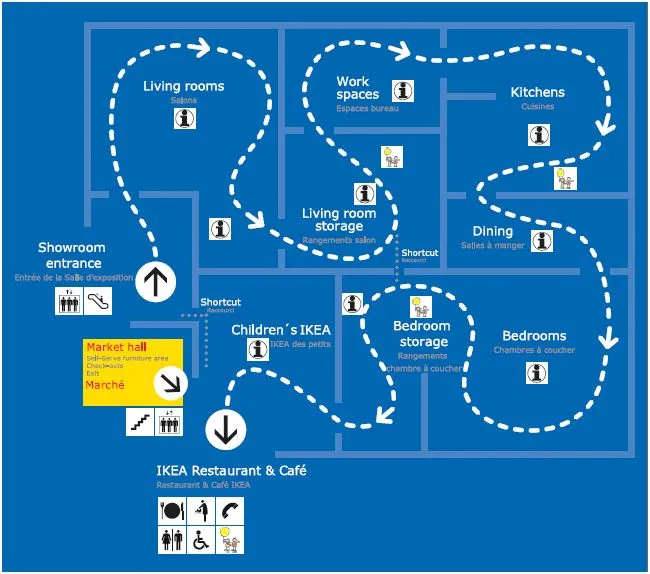

IKEA Blueprint

This layout wasn’t just practical—it was psychological genius. IKEA exploited the “Gruen Effect,” a phenomenon in which cleverly designed environments disorient customers just enough to make them lose track of time and spend more. By strategically placing visually appealing displays and lighting in key areas, IKEA ensured that customers would slow down, explore, and—more often than not—give in to impulse purchases. Research shows that the majority of IKEA purchases are unplanned, a testament to the effectiveness of this approach.

Another brilliant move was the division of the store into three distinct zones. The first section, the showroom, featured fully furnished rooms designed to spark ideas and help customers visualise how items might look in their homes. The second section, the “Market Hall,” offered smaller, affordable items like kitchenware and decorations—perfect for quick impulse buys. Finally, the self-service warehouse allowed customers to retrieve flat-packed versions of the furniture they had admired earlier. This system was not only efficient but also reinforced IKEA’s brand image as a do-it-yourself paradise.

But Ingvar didn’t stop at just furniture. He noticed a peculiar trend: after lunchtime, stores became noticeably quieter. To solve this, he introduced in-store restaurants that offered affordable, hearty meals like Swedish meatballs and lingonberry jam. The addition of food kept customers in the store longer, turning IKEA shopping trips into day-long outings. In some cases, people even visited IKEA solely for the food and ended up making unexpected purchases. This innovation blurred the lines between retail and hospitality, making IKEA a destination rather than just a store.

With these psychological and logistical strategies in place, IKEA stores became more than retail spaces—they became experiences. Customers didn’t just shop; they wandered, explored, and discovered. This combination of strategic layout, clever pricing, and added amenities created an unparalleled customer journey. By the end of the 1960s, IKEA had perfected its formula, setting the stage for global expansion and cementing its place as one of the most innovative brands in retail history.

Chapter 6: Controversies and Challenges

While IKEA soared, its founder’s past cast a shadow over its success. Ingvar’s youthful involvement with Sweden’s Nazi party resurfaced in the 1990s, sparking public outcry. Ingvar openly and honestly addressed his past, expressing deep regret and distancing himself from those views. Despite the controversies, IKEA’s employees and customers largely stood by him.

The company also faced criticism over labor practices, including accusations of using forced labor in East Germany. In recent years, IKEA has taken steps to address these issues, offering compensation to victims and implementing stricter supplier codes of conduct.

Chapter 7: Ingvar’s Legacy

Ingvar Kamprad, Founder of Ikea and Creator of a Global Empire – The New York Times

Ingvar Kamprad passed away in 2018, leaving behind a sprawling empire with over 450 stores in more than 50 countries. Despite his wealth, Ingvar remained frugal, famously driving an old Volvo and flying economy class. His vision for IKEA—to create a better everyday life for the many—continues to inspire the company’s global operations.

Today, IKEA is not just a furniture retailer; it’s a cultural icon, a masterclass in innovation, and a testament to the power of perseverance. From its humble beginnings to its complex controversies, IKEA’s story is a reminder that even the most iconic brands have a human side—flawed, fascinating, and endlessly inspiring.